Using Pracademic Approaches to Advance Digital Media Literacies

On February 22, BECID’s communication and media literacy experts, Inger Klesment and Gretel Juhansoo, delivered a public lecture at the University of Tartu, where they explored various pracademic approaches to enhance the digital media literacy of the general public. Inger and Gretel, known for their successful media literacy initiatives in Estonia, have primarily focused on engaging younger audiences.

Inger shared insights from her initiative, aiming to boost digital and media literacies in kids aged 5 to 10 through interactive play. Her science-based educational games encourage learning through activities and socializing. In less than two years, Inger has reached almost 6000 children all over Estonia. She has also been honored as the best media literacy educator of 2023 by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Science. You can learn more about Inger’s games on her homepage.

Gretel discussed an intervention called the TikTok House, initially a student project, designed with her coursemates Christina, Karmen, Anna, Katre-Liis, and Karoliina, at the University of Tartu, aiming to educate people about TikTok’s inner workings and data collection processes. The TikTok House evolved into a physical space intervention at Tartu’s Christmas Village in 2022, drawing around 40,000 visitors. The initiative continued with a second edition at the national Opinion Festival in Estonia in August 2023. You can read more about the TikTok House on BECID blog.

Why and how should I use pracademic approaches?

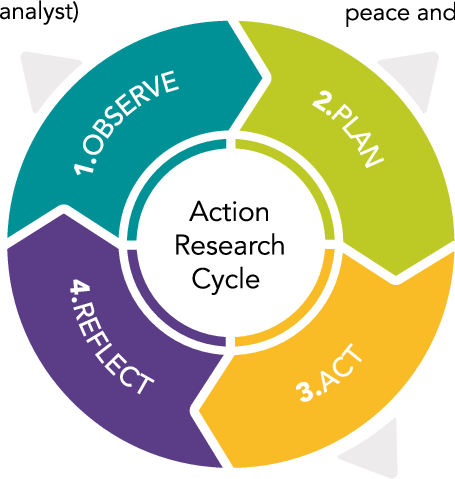

In their discussion, Inger and Gretel explored the reasoning behind using a mix of practical and academic, also known as pracademic approaches in digital media literacy education. They both agreed that the choice largely depends on educational goals and needs. Therefore, when designing any initiative, it’s crucial to thoughtfully consider every step along the way to select the most effective strategies for bringing ideas to life.

Jeong et al., 2012:

“Media literacy interventions refer to education programs designed to reduce harmful effects of the media by informing the audience about one or more aspects of the media, thereby influencing media-related beliefs and attitudes, and ultimately preventing risky behaviors.”

The lecture was based on Ofcom’s 2023 evaluation toolkit for media literacy initiatives, which the duo had broken down into five essential steps. Whether you want to build a TikTok-themed house or create educational games, the planning process of any media literacy initiative should include five distinct components: defining the problem, mapping the inputs, selecting activities, setting output goals, and considering potential outcomes.

PRO TIP: In each section of this case study, there will be an explanation of the purpose of the planning step, alongside insights from Inger and Gretel as shared in the lecture. We recommend taking a few minutes after each part to outline your idea for a media literacy intervention. By following the order of the case study, you’ll have a detailed plan for your intervention by the end of this reading material!

Defining the problem

To define the problem your intervention aims to solve, Inger and Gretel advise starting with research. Look into development plans, analyze current curricula and educational resources, and keep an eye out for opportunities to bring your ideas to life. Gain insights from your own experiences and social circle, and explore potential funding schemes for support. Depending on your project, checking statistics and understanding the current state of the world can add practical value to your media literacy initiative.

Inger and Gretel clarified that their focus on younger age groups guided their planning process, starting with an analysis of school systems and curricula. Their findings showed a lack of emphasis on media literacy education for 5 to 10-year-olds and algorithmic literacy across all age groups, highlighting a crucial gap. Defining the problem extended to personal motivation, with Gretel having just graduated from high school and feeling the lack of overall media literacy, especially within the context of relevant social media platforms and their data collection practices. Incorporating news on TikTok’s safety concerns and Inger’s insights into her children’s struggles added depth to both planning processes. Both Inger and Gretel analyzed various development plans to assess the relevance of identified gaps, especially in the context of Estonian pupils’ future studies.

Inputs

Mapping out your inputs involves a comprehensive consideration of the resources needed to address the identified gaps. During their lecture, Gretel and Inger emphasized considering your expertise vs. the expertise needed and taking into account your assets. It’s crucial to address essential factors such as time, financial planning, and making the best of previous experiences. Acknowledging support networks, exploring dissemination outlets, and ensuring the right staffing and infrastructure are beneficial for the most optimal and effective implementation.

Drawing from her experience, Gretel emphasized the significance of networking abilities and a willingness to take risks. Despite initial doubts about getting an exterior for the TikTok House at the Tartu Christmas Village, her readiness to face potential failure and thorough communication were what brought the initiative to life. Gretel also talked about the need for diverse skills within the project team. Since her group mates were skilled painters, she took the lead in conducting research, highlighting the collaborative strength of different talents. On the other hand, Inger’s key inputs involved materials from past projects and her extensive experience in working with children, along with establishing crucial contacts with schools. Both lecturers credited the University of Tartu for providing essential support and mentoring, further enriching their inputs, and contributing to the realization of their initiatives.

Activities

In general, media literacy interventions can be divided into two categories: physical space and online interventions. Within both, a variety of activities can be implemented, including challenges, contests, educational campaigns, and the formation of clubs or networks.

Inger strategically chose an educational game as the main activity for her initiative, drawing on her past experiences and the resources available at the time. She jokingly mentioned that even though she’s not an IT developer, her knack for playing games made the decision obvious. Gretel, on the other hand, went for an interactive physical space intervention based on research findings. She considered studies that highlighted the limited reach of online campaigns without financial backing due to platform profit models (Miller, 2021) and audience fragmentation issues (Papacharissi & Trevey, 2018). Additionally, Gretel acknowledged the possible skepticism towards information on social media, which could affect the trustworthiness of online media literacy campaigns (Literat et al., 2021).

Citations

Digital Moment. (n.d.). Educational Guide: Diving Deeper into Algorithms. Digital 2030 and UNESCO: The Algorithm & Data Literacy Project, Canada: Author.

Jeong, S. H., Cho, H., & Hwang, Y. (2012). Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of communication, 62(3), 454-472.

Literat, I., Abdelbagi, A., Law, N. Y., Cheung, M. Y.-Y., & Tang, R. (2021). Likes, Sarcasm and Politics: Youth Responses to a Platform-Initiated Media Literacy Campaign on Social Media. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12201

Milesi, C., & Franco, E. L. (2020). Volunteer contributions to building more peaceful, inclusive, just and accountable societies.

Papacharissi, Z., & Trevey, M. T. (2018). Affective publics and windows of opportunity: Social media and the potential for social change. In The Routledge companion to media and activism (pp. 87-96). Routledge.esponses to a Platform-Initiated Media Literacy Campaign on Social Media. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12201

Outputs

Although this is more of a statistical perspective after your intervention, planning out potential outputs is important to help you assess the impact and success of your media literacy initiative. Consider metrics such as the number of people attending or visiting your intervention, the number of different activities within your intervention, the number of downloads (if applicable), the count of workshops, seminars, or lectures organized, the growth in the number of new members in your network, the frequency of posts you create, and the overall duration of your intervention.

Inger brought up the importance of knowing the class sizes before organizing educational games for her initiative. The logistics of a game for five children differ significantly from one designed for 30, affecting aspects such as the quantity of physical materials to be prepared. For Gretel, planning the duration of the TikTok House for almost 2 months was crucial. It influenced the level of detail she could include, considering the potential risk of breakage or theft with a longer duration and a higher visitor count. However, being aware that the TikTok House at the Opinion Festival would only be open for 2 days allowed Gretel to incorporate more objects without worrying about security concerns.

Outcomes

Much like with outputs, the final step, outcomes, is more of a perspective aspect but still crucial to consider while planning your initiative. Reflect on the broader impact, including the potential for advanced media and digital literacy knowledge, the scope for socio-political change initiated by your intervention, and the possibility of new skills being acquired among participants. For yourself, consider the possibility of building expertise in a specific topic, expanding your network, and unlocking new opportunities for both the individuals involved and the initiative as a whole.

The duo expressed hope that their interventions have equipped Estonian youth with new skills, and knowledge, and provided innovative ideas for educators. They emphasized the significance of aligning media literacy education with the youth’s reality, steering away from outdated examples that fail to resonate with younger generations. Personally, Inger and Gretel value the outcome of working on new media literacy projects within the context of BECID, allowing them to voice the opinions of the youth and contribute to the ongoing evolution of media literacy strategy in Estonia.

In conclusion, the journey through pracademic approaches with Inger and Gretel creates a detailed plan for designing impactful media literacy initiatives. From defining the problem and mapping out inputs to selecting activities, setting output goals, and contemplating outcomes, the process involves a blend of research, creativity, and adaptability.