Teacher’s resource – scam deconstruction aid materials

Maria Murumaa-Mengel

Associate Professor of Media Studies, University of Tartu

maria.murumaa@ut.ee

Recently, schools in the Baltic countries have been spammed with bomb threats. Children, teachers, and parents alike are concerned because it is difficult to assess the veracity of the information and the likelihood of a real threat.

In a situation of information disorder, we are exposed to many types of information that may not be true and may be harmful to us:

Misinformation – information that is unintentionally false or misleading.

Disinformation – information that is deliberately false or misleading to serve the purposes of its creator or disseminator.

Malinformation – correct information shared with the intention of causing harm.

Students and teachers can improve their information literacy by trying to analyse the different types of information they come across daily and to understand why certain texts, visuals, and messages are more effective than others. The following article and test are about scams but can also be extended to the current bomb spam and information consumption in general.

Three simple principles to help protect against fraud and disinformation

Everyone can protect themselves from the harms of scamming and disinformation by following three simple principles proposed by social scientists Kristjan Kikerpill and Marju Himma from the University of Tartu, based on their various studies.

Police have again reported that scammers posing as police officers or bank staff are swindling people out of tens of thousands of euros. Or take the story about how a person was threatened that embarrassing photos of them, downloaded from the internet, would be shared – the victim paid, of course. And then there’s the case of a person who believed the information they saw on social media about an investment scheme promising high returns but which ultimately left the “investors” empty-handed.

You can tell seemingly educational stories endlessly, but they are useless. What is needed are universal principles. Kristjan Kikerpill researched in his doctoral thesis crime as communication and, more specifically, what kind of information supporting the prevention of falling victim to crime people get from the wording of online scams and manipulation attacks against them, for example, in a situation where somebody tries to cheat them out of money over the phone.

Marju Himma, a researcher in journalism studies, is participating in the media literacy project SMaRT-EU, which is looking at different ways for people to protect themselves from manipulative or damaging information. When discussing the issue, Kikerpill and Himma concluded that quite similar principles help protect against criminal manipulation attacks and disinformation campaigns.

Anyone can become a victim

“A fool and his money are soon parted.” That’s what you might think when reading yet another story about someone who has been scammed. “If you find the right situation, the right context, and the right vulnerability button to push at that particular moment, no one is one hundred percent safe from a scam. An unreasonable sense of infallibility and an overwhelming desire to gloat over victims are the characteristics of those who have not stumbled into the path of a skilled crook,” says Kikerpill.

“The same goes for disinformation or any other form of distortion of information,” says Himma. Fake news often feels more like the real news than the stories reported by the media. “The most common misconception is that the press spreads fake news, because if there is news, it must be journalistic,” Himma points out. Fake news in the meaning of disinformation is spread mainly through alternative media publications and social media. However, what they have in common is their emotional appeal: they attract attention with a threat or negativity and call for specific action.

“Just the other day, I clicked on an article on Facebook with a photo of Kaja Kallas, and the headline talked about losing self-control because of restrictions. The page had barely opened when I realised it was a fabricated page that installed malware on my computer,” Himma says. If a media researcher falls into this disinformation trap, it can happen to anyone.

Check the source but from a different channel

While the most common advice is to check the source of the information, this no longer necessarily works. Information disseminated for propaganda or damaging purposes may be entirely truthful. Still, the choices and emphases are made so that the constantly communicated stories leave a one-sided, often upsetting, disturbing and hateful impression.

“Information needs to be verified, and in most cases, a simple search engine will suffice initially. What does this tell us about the original source? Can the same answer be obtained from different, mutually exclusive sources?” Himma points out.

Kikerpill adds that when it comes to scams, it does not matter if it is an email, a phone call, or if the scammer shows up on your doorstep. It’s essential to check the information from another channel: in the case of an email, do not click on the link or attachment in the email, but Google the sender, for example. It is a good idea to check an allegation made over the phone by asking a family member or acquaintance or by looking for proof on the internet.

“Scamming is channel-neutral,” says Kikerpill. This means people should forget that certain scams are spread through certain channels. On the contrary, scams have universal characteristics regardless of the channel through which they are committed, and that is why a lie can be discovered by checking the information through another channel.

One of the common features of scams and disinformation is a call to action.

Notice that you are being prompted to act

Look at this exciting offer, visit this page, open the attachment, withdraw money from the bank, buy now, you are at risk too, give access, donate money, sign a petition… Do you see the common denominator? It is a call to action, either immediately or to prepare you to behave in a certain way in the long term.

“Clicking is also an act!” points out Kikerpill. Himma adds that in the case of disinformation, a person may be incited to vote in an election, to protest against (political) decisions, or to spread fear and panic, which, as you know, are spread by word of mouth.

Therefore, to protect yourself from scams and disinformation, you must immediately assess whether and what you are being asked to do. “If there is any kind of solicitation, you should critically check the information you receive,” says Himma. “And take your time,” adds Kikerpill: “Don’t rush, money doesn’t have to leave you in a hurry. In real situations where money needs to be transferred, deadlines are set, and you are allowed time.”

Scammers often take advantage of the pressure of time: “Make the transfer quickly,” “you can only make a big profit by investing now,” or “Your loved one needs help now.” Time pressure causes panic, in which people often cannot think clearly, take decisions, and act on emotion.

As the business model of scammers and disinformation spreaders is built on convincingness, they often take advantage of current events in society to increase the credibility of their messages calling for action. They provide the necessary background or social context for deceptive messages and disinformation. The context can be political turmoil, Christmas, or pension money just being made available.

Recognise when your emotions are being played with

Maybe you are familiar with those situations where a panhandler asks tourists on the street for €10 for his baby, who was born today. “He’s probably had a baby every day for the last four months,” says Kikeprill, recalling his experience with scammers like this.

Such situations are well thought through and rehearsed by fraudsters. They play on people’s emotions and have only one goal: to get the target to immediately act on instructions, such as clicking on a link or installing unknown software, and give the crooks what they want. Controlling the situation is crucial for scammers, a common feature of all scams.

Disinformation or any other misleading or damaging information evokes strong emotions. “It can make us oppose something or feel strongly about something. For example, an anti-vaccine activist is strongly influenced by an emotional story about the harmful effects of vaccines, and this may be the aim of the information disseminator – to convince people more strongly of the views they already hold,” Himma explains.

Scams asking people for money for a loved one who has had an accident or raising money for a seriously ill person who, after a quick search for information, turns out to be a fictional character are very common.

If the information you receive evokes sympathy, anger, sadness, fear, or other intense feelings and makes you react emotionally, consider whether it could be someone’s malicious intent to deceive or mislead you.

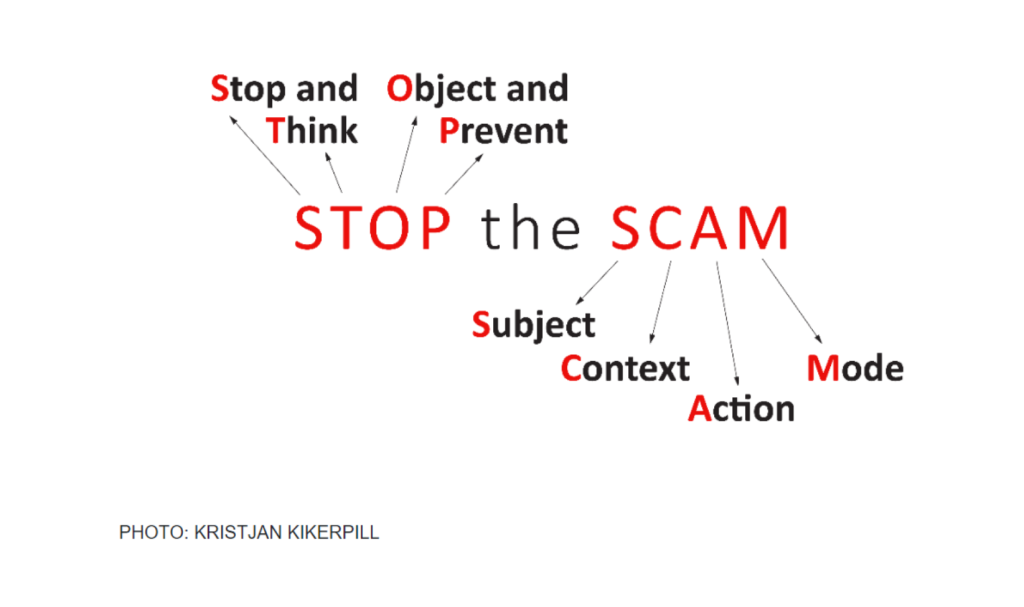

STOP the SCAM

Individual stories do not provide an opportunity to learn what to do differently. Instead, basic principles are needed to recognise potential scams. “You don’t just tell stories around a campfire. What is the purpose of telling a fairy tale? There’s always an educational aspect to it,” says Kikerpill. In his search for the common features of cyberfraud, he found this universal pattern that also applies to recognising disinformation. He has summarised it as a play on words, “STOP the SCAM,” where the essence of deception is summed up by the following keywords: Subject, Context, Action, Mode. Deception encourages action based on emotion.

Self-testing:

– via TV evening news programs

– websites of daily newspapers via their entertainment sections

– on the radio, where there is no time to check the news

– mainly through alternative and social media

– information evokes strong feelings

– news should be delivered with a smile

– cybercrooks are more successful when they are good-looking

– positive information spreads faster

– visit the same page several times to see if the information has remained the same.

– check the sources of information by clicking on hyperlinks and related stories in the article.

– see if similar information is available from other sources that are very different from each other

– consider using your head as the best method

– of course, I should click and help. I’m not some kind of psycho.

– I will call my mum and ask if she has sent me an email

– I will click on the link, but before I do, I’ll close all the other windows and tabs

– I will delete the email immediately without reading the rest of it

– scamming has universal characteristics, whatever the channel

– scams are usually presented in very neutral language

– all scams will be directed to all available platforms

– more channels should be created to prevent scamming

– throw your piggy bank at the monitor

– take time, because money doesn’t have to leave you in a hurry

– seize the opportunity, because money needs to circulate fast

– transfer the money as soon as possible and don’t tell anyone else, otherwise profits will be reduced

– joy – e.g. I have won a million euros!

– fear – e.g. if I don’t pay, my webcam recordings will be published!

– anger – e.g. the (NB! dis)information that the government wants everyone to get vaccinated every day, starting tomorrow

– desire – e.g. a gorgeous and sexy person asks you to buy them plane tickets so they can come and visit

– sympathy – e.g. the owner of a dog who stepped on a landmine needs help paying medical bills

– Sauce, Tofu, Onion, Pelargonium

– Scammed Out of Penny

– Scandals, Turmoil, Opinion, Paper

– Stop, Think, Object, Prevent