Notes from Bots: Replacing Human GPT with AI

Lilit Bekaryan, University of Tartu

August 2024

In lieu of an introduction

Back in 2023, when I was leaving my job in education, I shared an email with my network saying that I would be leaving soon and thanking them for all the wonderful years together. This was just a regular email that you must write when resigning to tell your network how much you’d like to stay in touch (even if you don’t). I was not expecting any sophisticated emails in return and was surprised to find one in my inbox that was quite long and sang dithyrambs in my honour.

“Your passion for teaching and dedication to empowering educators have left an indelible mark on all of us,” it said. “Your insightful lessons, thoughtful feedback, and unwavering encouragement have not only enhanced our skills but also inspired us to continually strive for excellence in the classroom. Your departure leaves a void that will be felt deeply,” it continued.

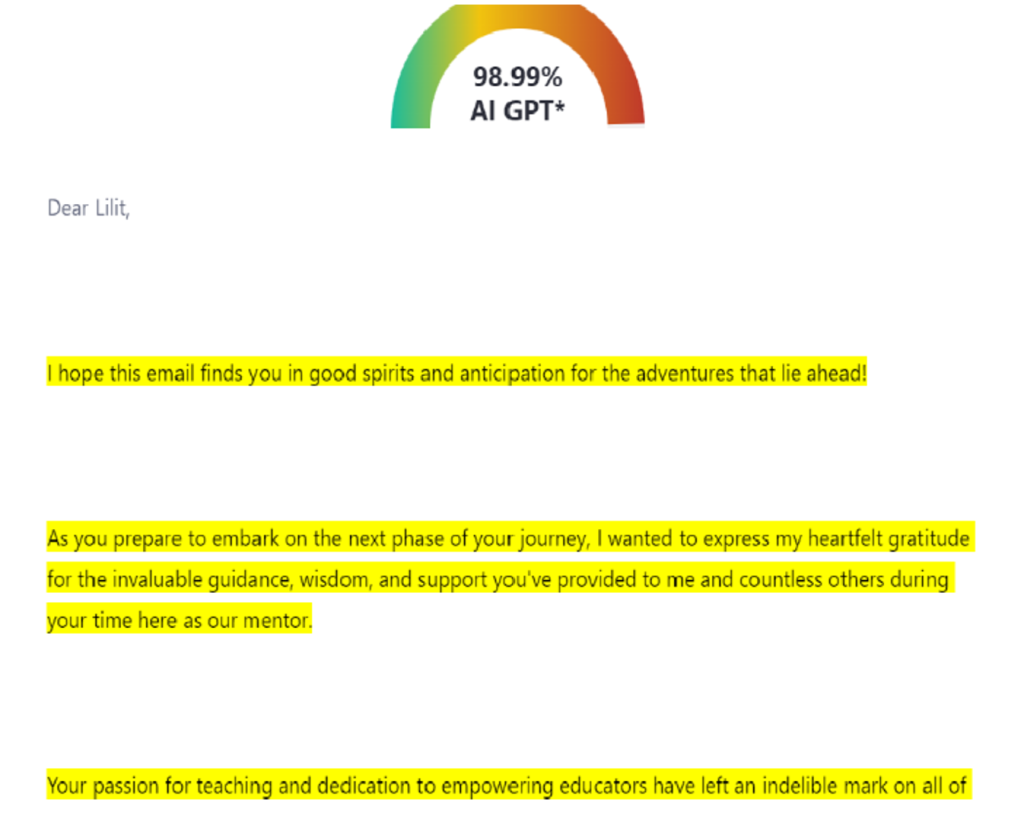

I was touched to tears but also had this nudging feeling of discomfort, thinking that I might not have deserved all this accolade. “An indelible mark?” Hmm, maybe. When you think back to all the home assignments you checked. “A void that will be felt deeply?” I had never thought of that, and the phrase made me feel responsible and guilty that I was leaving. However, as Rilke would put it, “No feeling is final”, as some gut feeling, which Gladwell would call a “deeply learned expertise” (Gladwell, 2006), pushed me to screen the text of the email on Zero GPT, an AI detector trained to detect Chat GPT and other large language models (LLMs). “Your text is 98.99 percent AI-generated,” it assured me (see Figure 1), and I sighed with relief and … disappointment.

Why did I feel disappointed? Well, I genuinely hoped that the sender really meant what they had written. Like everyone, I love hearing good things about myself. I also assumed that the message might have been generated under time constraints and the sender might have fed the LLM a general prompt seeking praise and adoration. Should I have felt disappointed, though?

As an educator, until recently, I had thought of Chat GPT and similar LLMs as educational tools that proved to be helpful when designing tasks for students and brainstorming discussion ideas. Now, I started questioning the ethics behind it. Suppose I use an LLM to design an emotional message or a social media post for personal purposes, does it genuinely convey how I feel, or is it simply the replication of the feelings the machine was trained to recognize in people and generate similar ones?

Also, where’s the guarantee that AI does not share the message it has generated for me with other users when asked for similar output? The terms of use that apply, for instance, to OpenAI, an AI research company behind the ChatGPT, state that between the user and the AI, the user retains their ownership rights in inputting the prompt and they do own the output.

However, when it comes to the similarity of content, the same terms disclose that due to the nature of the services and artificial intelligence in general, the output may not be unique and other users may receive similar output (OpenAI, 2024). Sadly, this may make any personal message drafted by AI predictable and inauthentic, since when using a general prompt to request a specific type of message, we may often get output that has reached or will reach many recipients.

Finally, how would one’s reliance on LLM for personal messages be interpreted in the 21st century, when a single problem can yield multiple interpretations: manipulation, pretense, misinformation within one’s social circle, or just a clear indicator of insufficient time?

What’s in an LLM?

The TechTarget network defines LLMs as a deep-learning algorithm that uses massive amounts of parameters training data to understand and predict text. Besides simple text generation, large language models can perform various tasks, including sentiment analysis, processing a text for a reader, answering questions, editing or translating content, etc (TechTarget, 2023).

In academic settings, LLMs have garnered a reputation of versatile tools. A recent study (AwadAlafnan, 2023) looking into the ways students and instructors use it concluded that students rely on the models for improving their search engine results, explore case studies, get ready and submit assignments, while educators consider LLMs as an opportunity to integrate technology in classrooms and support students with examples during the discussion. Researchers have also addressed worries related to the use of AI in science, especially with regard to academic integrity and plagiarism (Brown et al., 2020).

Nonetheless, there has not been much said about the social situations when people resort to AI to maintain their relationships with others or use AI for social situations that require verbalization of their emotions either in writing or in speaking. It seems fascinating to explore the reasons behind this behaviour. For instance, is it the absence of confidence, insufficient time, or sheer laziness that prompts individuals to turn to AI for seemingly straightforward and enjoyable tasks, like crafting personal or social messages for loved ones?

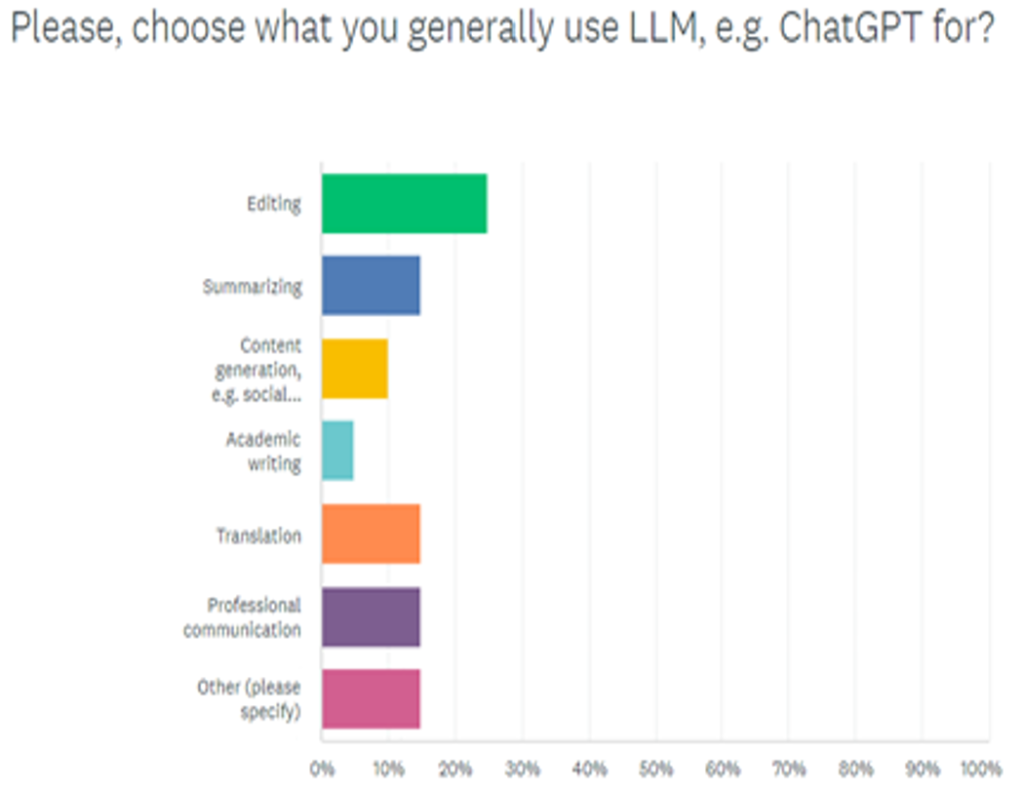

Fired by purpose

To get an answer to the question of what forces individuals to outsource AI to craft emotional messages, I conducted an online survey within my social circle using SurveyMonkey. The survey was open for 3 days and reached 90 respondents. The majority of the responses came from Armenia, and about 13 % of responses were submitted from the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Georgia. Half of the respondents confirmed they used LLMs for tasks that required them to somehow verbalize their emotions, e.g., creative writing, drafting a personal message, showing emotional support, or sending birthday wishes on a regular basis. Out of the listed tasks, congratulating people on special occasions was the most popular one among the respondents, while conversational therapy in an informal setting implying, for instance, a friend lending words of comfort to someone going through a breakup, came second right before writing poetry. Interestingly, no respondent chose ‘designing a romantic message’, but there were options like ‘highlighting the importance of the message, business communication, emails” listed among ‘other’ responses. About 36% of respondents mention the shortage of time as the key reason for resorting to AI, while convenience comes second (21%), closely followed by an exploration of creativity and lack of creativity with 19 and 16 %, respectively. Among ‘other’ motives, respondents also mention ‘laziness’ and ‘availability of support’ (see Figure 2).

Teasers for Thought

Since the official launch of ChatGPT3 in 2020, LLMs have been “the new black” in education. At the same time, some researchers have pointed out their potentially harmful implications. For instance, while GPT-3 may improve the quality of text generation and adaptability over smaller models, it also makes it hard to distinguish synthetic text from human-written one (Brown et al., 2020). Much concern has been voiced about the use of LLMs in academic education. Some researchers (Wahle, Ruas, Kirstein, 2022) identify the use of LLMs as a direct threat to the integrity of academic education, as sometimes it may be hard to identify if the produced academic content is AI-generated or human-written. Techno-optimists argue that it is not a student’s use of AI tools that defines whether plagiarism or any breach of academic integrity has taken place but rather the fact whether the student acknowledges the use of AI in the paper. Meanwhile, in a case study addressing text generators and academic integrity, researchers suggest the idea of “local ethics”, which they define as “a framework that is capable of exploring unique ethical considerations, values, and norms that develop at the most foundational unit of higher education – the individual classroom” (Vetter 2024; Cotton et al, 2024). It is also important to mention that while identifying AI-generated text is crucial to prevent misuse in plagiarism, fake news, and spamming, research into AI text detectors suggests that they might still be susceptible to errors as a result of spoofing attacks and paraphrasing (Sadasivan et al.,2023; Zhou et al., 2024). This implies that the deployment of unreliable detectors can lead to false accusations, mistrust, and other unintended consequences.

Outsourcing people for verbalization of one’s emotions is not a very new thing. Kings Philip II and Alexander, for instance, were known for their use of mocking poets at drinking parties to challenge and scare the powerful members of the inner circle at a court (Cosgrove, 2022). Allegra Kent, an American ballet dancer, mentions writing anonymous love letters for clients as a side job in her autobiography (Kent, 1997). A quick search on Google reveals A4 Chat Break Up text generator that positions itself as “a personal assistant for difficult conversations” and helps you craft empathetic messages based on the user’s inputs regarding the nature of the relationship and the reasons for the break-up. To avoid the so-called “bandwidth problem” (Kotsee, Palermos 2021), implying that teachers can only support and guide a small number of students at a time, teachers have proved to be effective in supporting students’ writing with automated scoring and AI-generated feedback (Drasgow, 2015; Crossley et al., 2022).

The ethical dilemmas here can be regarded from individual, organizational and societal perspectives. How would an individual feel if they learned that the texts they received were generated by AI? Would they perceive the sender differently, perhaps questioning their sincerity or emotional investment? Furthermore, if the recipient responded with AI-crafted messages themselves, how might the sender feel if they discovered this? Should dating apps or platforms serving as intermediaries for communication consider the integration of AI-detection tools into their architecture in quest of ensuring organic communication between the parties or should they not interfere? This raises questions about trust, but it doesn’t stop there.

Effective communication implies sharing information between two or more parties leading to the desired outcome. The information shared is conveyed and received efficiently without the intended meaning being distorted or changed much. One of the key components of effective communication is sharing emotions, which implies expressing the context, thoughts, and feelings that pertain to a certain emotional experience. The experience per se is rewarding both personally and interpersonally, as not only do individuals experience inner satisfaction and relief while sharing but they also nurture and fortify social connections through these interactions (Gross, 2015).

Research suggests that emotional intelligence involves the skills to identify and manage emotions within ourselves and others (Goleman, 2001). Some researchers differentiate between emotional intelligence and social intelligence, where emotional intelligence pertains to self-regulation habits, and social intelligence helps people build relationships (Bar-On, 2005). If we increasingly rely on artificial intelligence to craft our interpersonal communication, sidelining our social- emotional intelligence, what are the risks of losing it altogether? Some of us may be familiar with the concept of ‘cognitive laziness’ from organizational psychology, suggesting that one often ‘prefer[s] the ease of hanging on to old views over the difficulty of grappling with new ones.” (Grant, 2023) Similarly, can we assume that lending infinite credence to LLMs for social-emotional messages can make us emotionally lazy?

At the same time, by constantly feeding ‘emotions’ to AI are we inadvertently nurturing the development of its own emotional intelligence at our own cost? If yes, what is the potential for AI systems to be trained to generate emotionally persuasive but false narratives, which might lead to the spread of information disorders in online communication channels?

Another argument against heavy reliance on AI for mundane tasks can be a potential decline in creative thinking. Creativity experts suggest that one of the most effective methods to foster creativity is to treat it like a muscle (IDEA Fitness Journal, 2005). Just as muscles require training and exercise to prevent atrophy, individuals interested in maintaining or enhancing their creativity should actively engage in activities that foster creative thinking. At the same time, if individuals frequently delegate tasks to AI, they may become less inclined to engage in activities that stimulate creativity and problem-solving, which can decrease opportunities to exercise creative thinking. Can this overdependence on AI for simple tasks threaten human creativity while simultaneously undermining individuals’ confidence in their creative abilities?

These questions are intentionally open-ended and designed to spark deeper discussions among tech-enthusiasts and researchers.

What future holds

In a letter (1789) addressed to French physicist Jean Baptiste Le-Roy, Benjamin Franklin wrote, “…in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Were Franklin with us today, he would definitely add LLMs to the list. However unpredictable the repercussions of LLMs are, the models are embraced by an increasing number of users, and are welcome across all fields. In some cultures, it is common to anticipate danger before it arrives in hopes of preventing it. The recent implementation of the ‘EU Artificial Intelligence Act’ on March 13, 2024, prohibits practices that could jeopardize individuals’ safety, livelihoods, and rights. For instance, AI systems deploying manipulative or deceptive techniques or exploiting vulnerabilities, are prohibited. It raises the question of whether the AI Act could prompt individuals and communities to adopt ‘local ethics’ within social circles, promoting integrity and authenticity in social interactions.

Hopefully, this piece will not only initiate a discourse on the ethical considerations of integrating AI into interpersonal communication within social settings but also help identify the potential risks associated with using LLMs in social interactions.

References

AlAfnan, M. A., Dishari, S., Jovic, M., & Lomidze, K. (2023). ChatGPT as an educational tool: Opportunities, challenges, and recommendations for communication, business writing, and composition courses. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Technology, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.37965/jait.2023.0184

Bardis, P. D. (1979). Social Interaction and Social Processes. Social Science, 54(3), 147–167. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41886414

Brown, T., Mann, B. F., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Sastry, G., Askell, A., Agarwal, S., Herbert-Voss, A., Krueger, G., Henighan, T., Child, R., Ramesh, A., Ziegler, D. M., Jeffrey C.S. Wu, Winter, C., & Hesse, C. (2020). Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. ArXiv (Cornell University). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2005.14165

Cosgrove, C. H. (2022). Music at Social Meals in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148

Crossley, S. A., Baffour, P., Tian, Y., Picou, A., Benner, M., & Boser, U. (2022). The persuasive essays for rating, selecting, and understanding argumentative and discourse elements (PERSUADE) corpus 1.0. Assessing Writing, 54, 100667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100667

Drasgow, F. (2015). Technology and Testing. In Routledge eBooks. Informa. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315871493

Gladwell, M. (2005). Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Back Bay Books.

Goleman, D. (2001). The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in individuals, groups, and Organizations. Jossey-Bass.

Grant, A. (2023). Think Again. Penguin.

Gross, J. (2015). Handbook of emotion regulation. The Guilford Press.

Kotzee, B., & Palermos, S. O. (2021). The Teacher Bandwidth Problem: MOOCs, Connectivism, and Collaborative Knowledge. Educational Theory, 71(4), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12495

11.Parker, J. D. A., Reuven Bar-On, & Goleman, D. (2005). The handbook of emotional intelligence: theory, development, assessment and application at home, school and in the workplace. Jossey-Bass.

Perkins, M. (2023) Academic Integrity considerations of AI Large Language Models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 20(2).

https://doi.org/ 10.53761/1.20.02.07

Sadasivan, V.S., Kumar, A., Balasubramanian, S., Wang, W., & Feizi, S. (2023). Can AI-Generated Text be Reliably Detected? ArXiv, abs/2303.11156.

Strengthening your creativity muscle.” IDEA Fitness Journal, vol. 2, no. 7, July-Aug. 2005, pp. 61+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A134210796/AONE?u=anon~26b8bf36&sid=googleScholar&xid=9bd104a8. Accessed 12 June 2024.

Vetter, M. A., Lucia, B., Jiang, J., & Othman, M. (2024). Towards a framework for local interrogation of AI ethics: A case study on text generators, academic integrity, and composing with ChatGPT. Computers and Composition, 71, 102831–102831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2024.102831

Wahle, J.R., Ruas, T., Kirstein, F., & Gipp, B. (2022). How Large Language Models are Transforming Machine-Paraphrase Plagiarism. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main.62

Ying Zhou, Ben He, and Le Sun. 2024. Humanizing Machine-Generated Content:. Evading AI-Text Detection through Adversarial Attack. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), pages 8427–8437, Torino, Italia. ELRA and ICCL.

Electronic Sources

ChatGPT meme link was retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/posts/karishma-jadhav_chatgpt-meme-memeoftheday-activity-7105079225220575232-D1mB/ on 05.06.2024

Kent, Allegra. Once a Dancer …. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1997. (Kindle Edition)

Rilke, R. M. Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/95915-let-everything-happen-to-you-beauty-and-terror-just-keep on15.04.2024

https://www.ai4chat.co/pages/break-up-text-generator

https://www.curtis.com/our-firm/news/eu-artificial-intelligence-act-a-general-overview